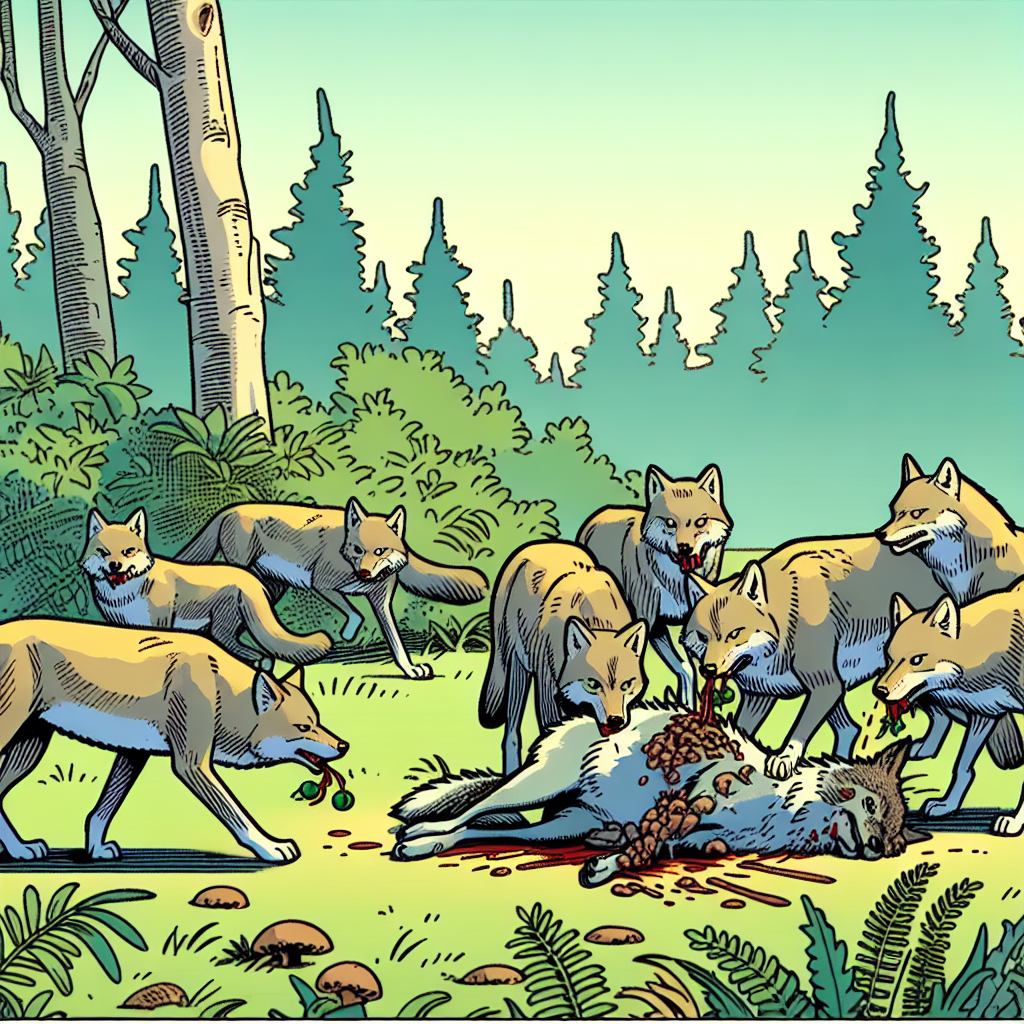

Grey Wolves’ Unexpected Hunting Behavior

The world of nature is full of surprises, and just when we think we have it all figured out, a new behavior or discovery completely shifts our understanding. Recently, scientists stumbled upon one such revelation: grey wolves on remote Alaskan islands hunting sea otters (ScienceDaily).

This behavior, never previously observed in these regions, provides fresh insights into the dynamic interactions between predators and their prey and opens new avenues for studying the ecological impacts on marine environments.

Wolves in the Waves: A New Predator-Prey Dynamic

The primary question on scientists’ minds is how these wolves adapted to hunt marine prey, linking land predators to ocean ecosystems in an unlikely dance. This relationship involves wolves shifting from their traditional terrestrial prey, such as deer, to a diet that includes sea otters. The wolves’ ability to swim and hunt in water not only demonstrates extreme adaptability but also suggests a potential shift in the region’s ecosystem dynamics.

Nutritional Rewards and Environmental Challenges

Sea otters, which have made significant recoveries from near-extinction in some areas, may now face new predation pressures. The impact of this on otter populations remains to be seen. Beyond providing a nutritional bounty, sea otters play a vital ecological role as keystone species; their predation on sea urchins helps maintain the health of kelp forests. With a new predator on the scene, the broader consequences on the coastal ecosystem bear close scrutiny. Scientists believe that understanding these dynamics can provide insight into the resilience and vulnerabilities of marine eco-communities, especially within changing climatic conditions (National Geographic)

Rewriting the Ecological Rulebook

The presence of wolves in the sea prompts crucial questions about what drives such substantial behavioral shifts. Marine environments pose numerous challenges, including diverse hunting methods and dietary requirements. Consequently, questions arise about how these wolves physiologically meet these challenges and adapt their behavior accordingly.

Scientists postulate several factors at play. Competition on land, reduction in traditional prey availability, and possible learned behavior transmitted through wolf generations—these are among the considerations being analyzed. Research from similar ecosystems, such as wolves in British Columbia, suggests the potential for learned adaptation in the use of marine resources.

Evolutionary Conundrums and Conservation Implications

Evolutionary studies on such behavioral changes have significant implications for conservation science. These findings highlight the complex interdependencies between species and the delicate balance needed to maintain ecosystem health. By unraveling the motivations and mechanics of these hunting strategies, researchers can better predict future shifts as environmental conditions—and predator-prey dynamics—alter with climate change.

Moving Forward: Implications and Future Research Directions

This unfolding narrative of grey wolves and sea otters serves as a reminder that nature defies simplicity. These discoveries demand a holistic examination that integrates marine biology, evolutionary science, and climate research.

Further research is needed to fully understand the ripple effects of this new predation on both land and sea ecosystems, as well as potential feedback loops, such as increased sea otter predation that impacts kelp forest health and, in turn, alters habitat structures for numerous marine species.

Ultimately, this new predator-prey relationship is not just a study of grey wolves or sea otters; it’s an exploration of adaptability, resilience, and the ever-evolving tapestry connecting life across what appear to be disparate worlds of land and sea.